An homage to Warren and Natalie — in title alone.

There’s photographic magic in the sun rising over a super-low tide. At the point where dawn meets a -2.0, the strange, the stunning, the predictable and the chaotic all converge on that plane of tide pools, mudflats, and beach hopper burrows.

One of my favorite coastal spots for tide pool exploration is Fitzgerald Marine Reserve on the San Mateo Coast. At low tide, the receding surf reveals an expanse of intertidal habitat. Fitzgerald is at once a testament to our coastal bounty, and an advisory against our exploitation of that coast. When you visit the reserve, you agree to a strict code of respect for the marine life which is hopelessly fragile under our feet. Among the guidelines: no collecting, no touching, no trampling.

Fitzgerald Marine Reserve - ©ingridtaylar

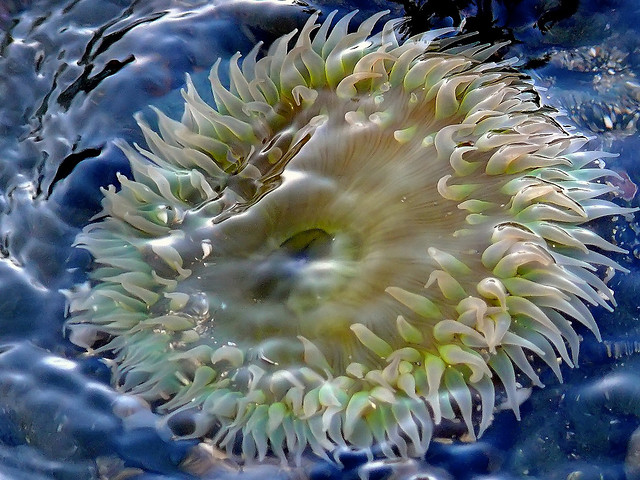

The reasons for the admonition become clear as each step reveals something crawling, digging, or simply breathing in stillness beneath a veil of seaweed. Whether at Fitzgerald or a less regulated stretch of coastline, the best policy is to never tread on anything but a bare rock — where you can clearly see what might be underfoot. These green and green-blue anemones were among several clustered in one of the pools:

Anemone – ©ingridtaylar

Anemone – ©ingridtaylar

Also clinging to rocky substrates in the pools, these echinoderms, a sea star (Ochre star, I believe) and a Sunflower Star:

Sea Star – ©ingridtaylar

Star – ©ingridtaylar

And … one of the sea stars food sources …

Mussel Bed – ©ingridtaylar

Along the Sonoma and Mendocino Coasts, the quest for abalone renders the tide pools less sacred. During a recent -2.1 at sunrise, we witnessed hundreds upon hundreds of abalone divers swarming the tide pools in wetsuits, with the unmistakeable, neon donuts on their backs — their abalone floats.

Abalone Diver – ©ingridtaylar

Abalone Divers – – ©ingridtaylar

Beyond the trampling that occurs when this crush of humans pounds the habitat, abalone poaching is a real and distressing problem on the Mendocino Coast . . . one which engaged the passions of a number of locals who were kind enough to fill us in on the history of legitimate abalone diving and acquisition in the area. Unless you’re sporting those khaki Fish and Game credentials, there’s no way to assess how many of the divers are abiding by the three-abalone limit or the 24-per-year sport abalone ceiling. Commercial abalone diving in California is illegal, as is the purchase of wild abalone.

The parking lot below, taken on Highway 1, was a scene replicated at almost each coastal entrance that morning at low tide, just minutes after sunrise.

Abalone Traffic – ©ingridtaylar

And then there’s this, an unfortunate but unsurprising souvenir of the morning:

Cigarette in Tide Pool

Among the marine life in Mendocino — waiting out the low tide until the ocean reclaims it to safety — is a variety of mollusk species, like this Black Turban (Tegula funebralis). It’s a seaweed-eating creature which, according to my copy of the Beachcomber’s Guide to California can live up to 100 years.

Black Turban – ©ingridtaylar

One of my best low-tide experiences happened closer to home at Emeryville Crescent. During the winter months, when migrating birds turn San Francisco Bay into an avian party — and when a sudden stream of advection fog creates instant spook and atmosphere — shots like this come to characterize the taciturn thickness. The myriad dots in the photo are diving ducks, Scaup. In the silence of this scene, the lapping of their bills against the water — and the occasional cry of an egret are the only sounds breaking that atmospheric wall.

Egrets + Bay Bridge – ©ingridtaylar

As the tide recedes, throngs of shorebirds follow the moving shoreline in search of the crustaceans and organisms now laid bare and ripe for the picking. I snapped this egret turf battle as both Great Egrets and Snowys staked out their pools of marine dining.

Low tide becomes a canvas of mixed shorebirds — sandpipers, avocets, godwits, plovers, curlews, Dunlins and Willets. They flood the mud and erupt in a flush, deflecting aerial predators with a collective flip of the flock.

Shorebirds in Flight – ©ingridtaylar

[…] Fitzgerald Marine Reserve picture: https://www.thewildbeat.com/2009/06/17/splendor-in-the-low-tide/ […]

[…] Fitzgerald Marine Reserve picture: https://www.thewildbeat.com/2009/06/17/splendor-in-the-low-tide/ […]