Originally published at The Wild Beat in 2013

I stepped out of a mist and I knew I am. I am what I am. And then I thought, ‘But what have I been before?’ And then I found that I had been in a mist, not knowing to differentiate myself from things; I was just one thing among many things.”

~ Carl Jung, The Red Book

I used to think about Jung and bird dreams whenever I watched rafts of ducks sleeping on Lake Merritt in Oakland, their heads tucked back under wings as they swept the lake like feathered Roombas.

I wondered if they were, as Jung suggested about human dream states, creating psychic wholeness by connecting their conscious and unconscious realms. Externally, for us, there’s serenity in birds flocked together for slumber … Canvasbacks revealing just one wary red eye, Ruddy Ducks spinning with their sail of a tail, Scaup males waking before the rest and rustling the females to breakfast and mollusks. They utter the lightest peeps in their own language as their unconscious dream life meets life’s surface tension.

In the comments section of a 2001 MIT newsletter, a reader asked:

“Does the ability to dream require a level of self-consciousness or at least the ability to conceptualize an objective world-view? How, otherwise, does the animal brain construct a dream experience that is not a carbon-copy of events simply regurgitated through synaptic pathways, but a ‘creative’ narrative employing events and data in a new narrative?”

This question was in response to a study where MIT researchers found that rats who’d been trained to run through mazes, exhibited brain activity in their sleep which suggested they were re-processing their day’s events, or collating multiple events, to produce the same brain response as if they’d been running the maze physically.

At the University of Chicago in 2000, researchers working with Zebra finches found similar replication of brain-wave activity in bird sleep. They concluded that the finches were rehearsing their songs in their dreams, possibly related to enhanced success in mating, given the song’s importance in courtship.

So, when ducks dream, do they replay their best dives and dabbles? Do they work through the trauma of evading a hunt, or evoke all sensory pleasures in memory of distant rice fields? Are they forming universal and species intelligence through some process of the collective unconscious, like the 100th monkey learning to wash sweet potatoes? Or are they releasing their brains to create something magnificent and transcendent that their feathered, webbed bodies can never manifest on this earth plane?

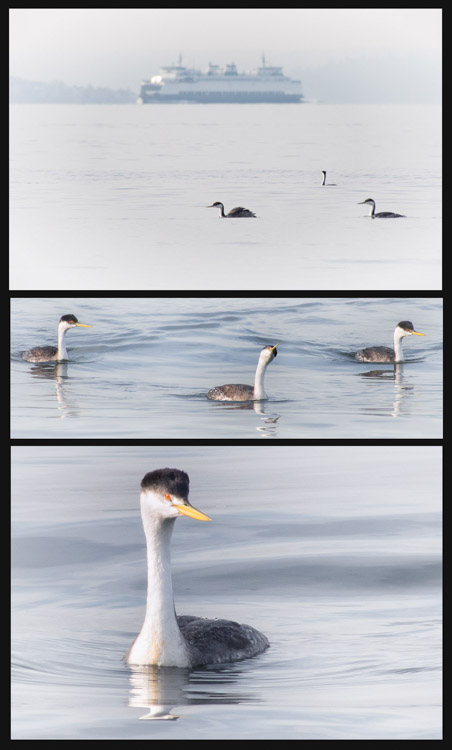

Last month, I saw a flock of Western Grebes floating on Elliott Bay, their necks all tucked into plumage in characteristic S-curves. A work boat sped past their raft and jolted the crew out of slumber.

Grebes + Boat

You can barely see the grebes behind the boat in this crop.

closeup

Through my telephoto lens, with distance compressed, it was difficult to say just how close the vessel got, but it was close enough that the grebes scattered toward me and the shore.

I think about how often this occurs in their lives — and how precious a night it is, for those of us lucky enough to sleep without having one eye open, without our plumes bristling in the wind. That is, to sleep in a fully altered consciousness, in a bed, undisturbed by predation or guns or weather or hunger or motor boats.

Lao Tzu said that “life is a series of natural and spontaneous changes. Don’t resist them; that only creates sorrow.” In my time with our wild brothers and sisters, I have concluded that they are better attuned to this flow than we’ll ever be, whether one attributes their facility of adaptation to instinct or enlightenment. Watching birds sleep and dream and then be roused — and then reform like a galaxy, swirling back into rafts on a distant swell — makes me believe that they know they are “just one thing among many things,” as Jung declared. Even as they are firmly rooted in their individual survival, they organize their experience around the unity of an avian archetype. Perhaps they are aware that existence is ephemeral, their heightened sense of danger a burden, but also an antidote to the complacency that allows us to do things like drive motorized vessels through rafts of dreaming birds.

[My grebe shots were photographed with the Olympus OM-D + Lumix 100-300mm. In the middle photo, the center grebe is looking up at an eagle passing high overhead. The collage was post-processed in Lightroom and Photoshop. The Lake Merritt images were shot with my Olympus E-3 and 70-300mm lens.]

In Dreams ~ Roy Orbison (& Blue Velvet)

How do you do it, Ingrid? Take so many perfect photos of so many lovely birds? Know so much about so many subjects? Find time to weave facts and thoughts and images together into an informative and delightful blog?

I learned what Roombas are, thanks to you.

Say, there’s a similarity between the way the gorgeous Canvasback sleeps and my Boxer friends’ half-shut eyes.

Blessings from your birder-in-the-making friend.

Thank you for the kind comment, CQ. Now, if I can be so humble, there are, indeed, a few photographers who comment here, whose images are genuinely perfect. I aspire … but am reconciled to my fallibility! 🙂 Maybe one of the greatest aspects of nature photography is the time you spend in communities outside your own species. In the absence of verbal repartee, a process of silent rumination and interaction takes over. Admittedly, I fall into some element of psychoanalysis, wishing I could know with certainty what their experience really was, and thus pondering what it *might* be.

I like how you composed the vertical triptych, how from the distance, the grebe gets gradually closer. As to “just one thing among many things” from Jung, I also think of it as a “synchronisation” with the environment, at the unconscious level. It’s as if losing one’s ego and becoming a “collective” itself. I’ve watched this by looking at monogamous pairs of geese and swans. They swim in a perfectly synchronised manner, and they do this unconsciously. They synchronise their movements identically to the point of becoming “one”. Could this also respond to what Konrad Lorenz wrote about “imprinting” in geese?

Jung and Freud disagreed, specifically about the “unconscious” in general, whether it was the personal (Freud), or the collective (Jung). I tend to think that what Jung wrote is more easily understood in the light of how you’ve expressed it in this article, with animals. As much as I disagree with Freud’s libido theory, I believe he was right about one thing: humans exclusively respond more to the “personal unconscious” than animals. Animals are able to flock, and form a “collective” behaviour response. Humans need to analyse first, and think as individuals. They need to “transcend” or “overcome” their egos first, in order to evolve emotionally or spiritually, and manage the “pleasure principle” which Freud first introduced.

As for animals dreaming, I definitely think they do, and they must have their “avian” archetype in their unconscious, but when they awake, they respond to environmental circumstances. Humans dream, but may awake having to go to a psychiatrist because of a particular dream they had. Here’s where Freud steps in with his “id”, based on what he called the “pleasure principle” or “libido”. He believed dreams were repressed memories and events. Jung actually based his ideas on Freud, but removed the “personal unconscious”, and excluded the libido theory. He simplified concepts that were complex and needed to be viewed within a larger perspective, and not related to the “pleasure principle” which Freud so much advocated. Humans, however, continue to respond to “pleasure principles”, this why Freud continues to be considered a “father” to psychoanalytic theory, and Jung the founder of analytical psychology.

I was going to ask the same question as CQ, how do you do it Ingrid? Your posts are always at once, thought provoking, beautiful, and informative. I hope that birds dream of all the good things in their lives. Bath time, mating, ripe fruit on the vine. I hope they don’t take things for granted like some humans tend to do. Always thinking of themselves and not considering the collective good.

There are some humans that think they are superior to other animals. Do you think there are some animals that think they are the superior creatures? I have witnessed the speeding boat through the raft of grebes, even nesting grebes. Besides enraging me, it makes me wonder, what prompts this type of behavior?

Philosophizing aside, I love your photos. The sleeping ducks at Lake Merritt immediately calmed me. Then the one-eyed Canvasback brought me back to the reality that birds are always on the alert from danger. They may not know from where it may come, but they know it’s out there. I have seen that partially opened eye as the bird’s hidden webbed feet slowly carry it away from the unknown human.

When I saw the diving Bufflehead drake, I said to myself, there is that shot you’ve tried so many times to get and failed. They dive so quickly. The shot of the grebe looking up reminded me of my yard birds today as I was out taking some photos and, at once, all the birds flew off in unison, as I looked high in the sky overhead to barely make out a Sharpie flying over. In the collective, some individuals are always on high alert!

Interesting speculations, Larry! I can’t imagine any animal thinking itself superior to another individual or species — or thinking merely of his own welfare instead of the collective good.

But if any creature does act like he’s lording it over another, this wouldn’t represent his true nature, to me. It would be, in my mind, a distortion — a false belief in brutishness or bestiality or [insert any negative trait], temporarily masking his real self. On a number of occasions, when I’ve refused to accept the guise of wrongdoing (in man or animal) and insist upon seeing the good — well, sure ’nuff, the good comes pouring out. We must try that out on our view of hunters, huh? Governed by unselfish regard for all life, they really want to be shooting not a gun or a bow but a camera! 🙂

Ingrid may laugh at me, but I believe that one day all the animals will be able to sleep in peace, unafraid, undisturbed, with both eyes fully closed.

Larry, the birds you share with us are elegant expressions of Life! Having just finished the chapter on turkey vultures in a book the Wild Beat blogger and I have both read, I was thrilled to see that gorgeous creature atop your photo lineup. I can’t call him my favorite, though, since each individual is so beautiful to behold. Their Creator must very satisfied with His/Her handiwork.

The basement damp-proofing tips on [url=https://domograph.ru/]domograph.ru[/url] helped me select the right injection sealant for hairline cracks and taught me how to apply waterproof plaster correctly. My walls have held up through months of heavy rain without any leaks.