Boundary Bay, British Columbia

Edited to add (2/17/12): Since I posted this, I’ve had animated discussions with photographers who disagree with my stance on this owl/space/ethics issue. They’ve told me it’s acceptable for photographers to be out in the marshes, as long as they don’t flush the owls. I wanted to find out what the “official” policy was, irrespective of my personal feelings. So, I called the regional office to get their take. The person I spoke with said their policy is that they do not want anyone out there, despite lack of enforcement. The signs are their best effort to discourage this behavior. But, because the land is Provincial, they have no control over that section of habitat itself. The bottom line is — they do not want photographers in the marshes, for the owls’ sake and for the sake of the habitat. They want people to stay on the dike and trail only.

Related post: Snowy Owls, Boundary Bay & Rethinking My Own Motivations

——————————-

I loved meeting this year’s Snowy Owls. What a privilege to be part of their world for even a short time. In my next writings, I’ll post a few of the photos we took while watching the owls lounge on driftwood perches up at Boundary Bay in British Columbia.

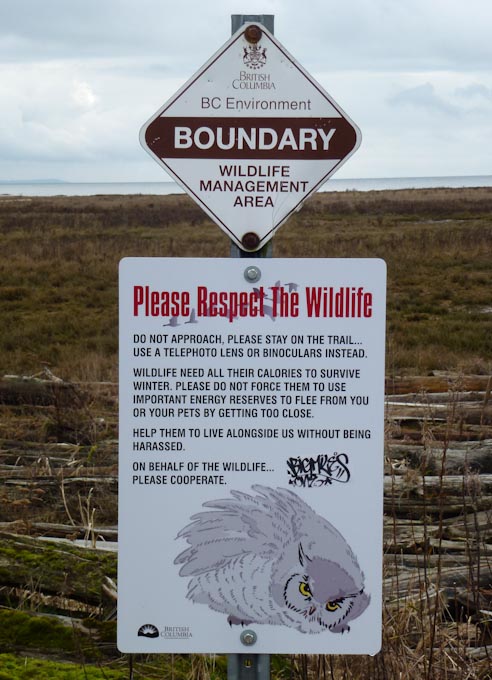

I’m posting these cautionary signs first, so I can explain the situation up at Boundary Bay if you haven’t been. Tune out now if you don’t want to hear one more [minor] rant on wildlife photography. This relates to the video I posted the other day about photographers and Snowy Owls in this area.

Part of the reason it’s taken me this long to go see the Snowies is because I deliberated over whether or not to add myself to the fray of owl watchers. After talking to several people who had been up to Boundary Bay, it sounded like the initial frenzy had subsided and there was a decent balance between viewing the owls and the owls’ personal space. So, on the first predicted sunny day in a week, we mustered the 5am departure and headed for the Peace Arch border crossing.

Once at the park, there’s a dirt lot where you park, then an approach to a dike which overlooks a vast expanse of wetlands toward Boundary Bay. It is a dream of a habitat for shorebirds and for the Northern Harriers who skim the grasslands in search of voles. It’s also the spot some Snowy Owls chose for their wintering rest — part of the Snowy Owl irruption that hit the lower 48 this year.

The terrain reminds me a lot of the wetlands around San Francisco Bay — except for the presence of the 50 or so Bald Eagles we saw throughout the day who were often hunting (and missing) the gulls hanging out in farm trenches. The gulls, unless taken unawares, can outfly the eagles.

The gravel trail where you view the Snowy Owls gives wide berth to the habitat within. There is, however, a large section of driftwood perches and snags where a number of the owls choose to sit, preen and otherwise do Snowy Owl things close to the dike trail. This is the spot where most people hang out and enjoy the spectacle of this year’s irruption.

These two photos give you a sense of place. Hugh shot this first image, using me (bundled up, with hand warmers in my pockets) as foreground. In the second, I’ve pointed out some locations of Snowy Owls on the driftwood.

Boundary Bay Trail – ©hughgrew

Boundary Bay Trail – ©hughgrew

I’m not sure how it was back in December, but by now, the trail is clearly marked with various warnings about staying on the path to avoid harassing or approaching the owls.

Although most of the amassed birders and photographers respectfully abided by the postings, there were still quite a few photographers out in the field/habitat area throughout the day, venturing closer to the owls for their shots.

One photographer (not pictured) flushed an owl while we were there. And when you watch the owls’ reaction through the tele, there are often subtle signs of alert, even if they don’t move in response.

The owls expect people on the paths — those are the normal noises of this world. And even though I understand human presence can cause stress in any context, even on designated pathways, I do believe it’s quite different when they have to respond to lurking threats from unexpected angles and approaches.

We talked with one photographer coming out of the field, reminding him how important it was to stay out of that area and let the owls rest, away from human intrusion. Two owls were recently brought into a nearby rehabilitation center, emaciated, and I was told it’s possible that constant interference is inhibiting their ability to build reserves for the migration home.

This guy said he knew full well that he wasn’t supposed to be out there but he wanted to be closer. Others were too far out into the marsh to reach without distressing the owls ourselves. So, it can feel like a bit of a helpless situation — when you see other photographers approaching too closely, putting the owls on continuous alert — but not being able to do anything about it for fear of causing the same disturbance.

What those photographers don’t realize is that they were also setting a bad example for people out walking who didn’t know any better. I heard one woman say to her husband — “why don’t you go out there for a closeup shot? Those other photographers are out there.” He was a carrying point-and-shoot with no zoom, and thought better of it. But throughout the afternoon, we saw several people with point-and-shoots, creep closer to where the big lenses were.

Most of the photographers in the field were hauling 500mm, 600mm and 800mm lenses, some with teleconverters. It’s not the same as having a birding scope, that’s true. The reach isn’t nearly as far. But they could have easily stayed on the path and still had some beautiful shots with their glass. Of course, the shots from the dike are the shots everyone else gets, so I understand why the photographers are out there. The backgrounds are better from the marsh, and the shots lend themselves to spreads on nature photography sites and in portfolios.

Those images are spectacular. But, I believe there’s another cost to be considered when padding the portfolio, and that is the duress of human pursuit from the wild animal’s perspective. That’s why I personally think the measure of any photograph must include a balance of personal acquisition versus the cost or benefit to the subject, particularly now that there are so many photographers with the gear and the motivation to get that shot. It gets crowded out there.

I’ve looked at some Snowy Owl photos online and there are quite a few which look to be shot in-field. At least one well-known pro took his field group into the marsh for a workshop. I came upon a few such images on Flickr, too, with multiple pages of comments from viewers. I’ve seen similar shots submitted to online birding magazines. Those are the photos that get published and the solution would be for magazines and venues to insist on an ethical standard or baseline when it comes to the images they choose. Short of that, it’s an element of education and respect for wildlife. There will always be people who engage wild animals in utilitarian fashion. But my hope is that as we gain greater proximity through our lenses, the moments themselves — of being, say, with the Snowies on a frost-glazed Canadian day — will be far more important and poignant than getting the representations of those moments on an SD card.

Related Posts: Staging Nature Shots | Wildlife Photography Ethics Matter | Marine Mammal Viewing From a Distance |

Ingrid, this is an excellent post and I feel that I was standing right next to you on the pathway reading this, your words brought me there. It still breaks my heart that some photographers “will do anything to get the shot” even if that means stressing an already over stressed bird or harassing the birds so they will do “something”. The photographers that go to locations like Boundary Bay should know that when they are standing side by side that they will get very similar images, it still should not mean violating the posted guidelines to get something different.

Thanks for going and for sharing your experience with the Snowy Owls.

Mia, thanks for the note of support. I’m kind of surprised how many photographers I’ve spoken with since I wrote about this issue, who are resistant to the idea of staying out of the marshes. I had one tell me, “I have no problem with us photographers being out in the marshes.” He alluded to getting better, uncluttered background shots. Uh … but do the owls and the parks department have a problem with it? (lol). Anyway, I appreciate the vote of confidence. On this particular issue, it seems more people are in the gray area than in the black and white. The owls are much more contentious than I realized. d:-)

Ingrid,

Some photographers are in it for the money that they might get from a photograph with fewer distracting branches or blades of grass, but I feel the bird (or animal) is always more important than a photo. The marshes need protection from people stomping the vegetation down, the birds need protection because they do not need more stress or to be harassed. Stress the birds so much they die, then what is left to photograph? Its carcass.

Mia, what’s your estimate on how many of these guys are pros, in terms of making a living at the photography? Is there any good way to assess that? I ask because after we had this experience, I went looking for photos online, just to see where they were being used. And I saw quite a few shot from this field vantage point, that appear to be posted for Flickr commentary. One guy had three pages of Flickr awards and “you’re awesome” commentary. His bio suggested he was a hobbyist. Another had submitted a few of these photos to a birding magazine, but they were in a reader-submission forum, not published in the magazine itself. And I know a lot of smaller magazines pay on the scale of, say, $100 a photo. I guess it’s the potential they see in the photo — contest winners, resume-builders, and so forth. I see contest-winning images sometimes that make me question how the photographer got the shot, and I actually think it should be standard practice by magazines and contests, to verify the methodology. Dream on, right? We are living in a material world, as Madonna reminded us.

Ingrid, most bird photographers are not making their living just selling their images, what they are making money with is giving photography workshops, writing how to books or selling CD’s/PDF’s with information on certain locations. For instance; $50.00 for a CD on where to photograph birds at Fort De Soto (it is not that big and not hard to find the birds). Or charging several thousand dollars per person for a weekend instructional photography class. It would be difficult to make a decent living just selling images.

I know I have seen winning images in contests that make me question how the photographer got the shot, if they did it where they said they did it (example: some are confined to National Wildlife Refuges) and how much photoshopping has been done to the resulting image. Some contests state you must follow ethical guidelines found on either the ABA site or NANPA. I’m not sure those are always followed either.

I’ve read that some publishers have stopped publishing images where the bird was baited or when wildife images were taken at “game farms”. I know that some magazines ask you to sign a statement that says you have followed ethical guidelines published by NANPA or the ABA.

Then there is the question of how to determine who is a “pro” photographer. Some say it is 50% of your combined total income. Some say 10%. Some people say you are a pro if you have had images published. Each person’s perception of what is a “pro” seems to be different.

Hi Ingrid,

You found my blog post regarding this issue so I wanted to reciprocate. I’m a landscape/nature photographer first and foremost but the snowy owls have received so much attention this year that I decided to head up to Boundary Bay to try my luck. This was my first visit ever to this location and I have to admit that I did venture out into the marsh to check things out. As I spent time out in the marsh, I felt less and less comfortable about my being out there. I did see the signs about the owls (both at the kiosk and along the dike) but, quite frankly, the signs use “please” instead of more forceful language.

It’s not surprising that the agencies don’t have the resources for enforcement. I do think redesigned signage with more explicit language (i.e. “it is illegal to enter the marsh”) could be done with not much cost. Also, the two “entry” points down into the marsh where the owls congregate should have more substantial woody debris structures to discourage entry. A large structure, along with a sign you have to physically get past would leave a photographer little room to use “I didn’t know” as an excuse.

I will return to Boundary Bay at some point but I will remain up on the dike.

Steve, thanks for coming by. Your perspective is actually more broad than mine because you have the experience of both locations in terms of the owl photography. Do you know what it was about that experience specifically that made you progressively more uncomfortable?

One of my Flickr contacts mentioned the same thing you did — that people who are determined simply would not respond to the courtesy of “please” in the signs. He suggested penalties and fines. I wonder if it’s my European upbringing that interprets “please” as more of an imperative. [:-)

In my conversation with the parks official, it appears any such admonition would have to come from the Provincial department that owns the land. And, as some photographers have pointed out, during the hunting season (when they were there), that area was open to waterfowl hunters — and the photographers felt they were causing far less disruption than the shooting already going on in the field.

I agree with you, too, about the signage. It should be distributed more widely and have more forceful language. I had a discussion with one photographer who took umbrage with my words because he said that many photographers out in the marsh didn’t flush owls. Two of the signs merely say that: if you flush owls you’re too close. Those signs also say “please don’t approach” but it’s become quite clear from myriad conversations I’ve now had, that the word “approach” is even open to wide interpretation as others see it. So, I hope the Snowies stay away next year and give themselves a break. But if they do return, I would impress upon the park department to alter the methodology and gear it toward those very loopholes.

Boundary Bay is such a gorgeous place, filled with harriers and shorebirds and Bald Eagles and a terrain that reminds me so much of my Bay Area home. I loved every natural aspect of my visit there.

I generally consider myself a law abiding person so I guess my initial uncomfortable feeling was due to the legality of just being out in the marsh. The signs seemed to indicate that it wasn’t allowed but as we’ve previously discussed, the language on the signs isn’t clear enough. Based on your comment about allowing hunters into the marsh, the legality of access is just contradictory and confusing.

Anyways, after being out in the marsh with the other photographers, I just began to wonder if I was getting too close so I just backed off and left the marsh. Again, I won’t be specializing in wildlife photography so I suppose I’m not as vested in that whole “get the shot” mentality.

You are so right about Boundary Bay being a special place. I’m also looking forward to returning in the future!

Tsk tsk Steve.

I live in BC so I guess I am more familiar with that sort of signage – if I see a Ministry of Environment (provincial) sign that says Wildlife Management Area I know to stay out. I also went there on a few field trips during my University days (BSc. in Biological Science) and we learned about the species and delicate habitat there. At the very least this is not an alpine environment and the longer growing season does mean that things can bounce back faster. I know Steve is quite familiar with Picture Lake and Artist Point in Washington and the damage there – and that takes years and years to start growing back.

https://env.gov.bc.ca/bcparks/explore/wma/boundary_bay/

The first paragraph says it all for me – Purpose of Wildlife Management Area: Conservation of critical, internationally significant habitat for year-round, migrating and wintering waterfowl populations, along with important fish and marine mammal habitat.

Now like I said I live here, so I know a bit more about this I guess – but I do find the language on the signs somewhat weak. They do not want people in there, especially for unsanctioned activities but the sign merely suggests the area is “managed”. That could mean a lot of things. They could be clear that this is not an area you can go into…

I also think that “if you flush the owls you are too close” gives way to the argument that you can only know you are too close if the owls fly away. I could have flushed an owl on the trial there, but I think what we are generally talking about are the photographers who do this on purpose to “Get the shot” and this is what I have a problem with. I think you’ve both seen the youtube video showing this.

This years owl irruption is almost over so the owls will very soon be gone from Boundary Bay but I think next time this happens (every 4 to 5 years I think?) I will get on the case of the City of Delta and the Ministry of Environment as to what is legal and perhaps issuing better signage to indicate this. I’d love for them to sweep through (even if for just one afternoon) early in the season and pull people out of the marsh and/or fine them. I think that might go a long way in keeping things in better shape for the rest of the season.

I just re-read that owl sign – it DOES say to stay on the trail. Normally I just see the top sign – the Ministry of Environment one. The owl sign is pretty specific.

..and at the bottom of the sign it says “please cooperate.” A little different than “thou shalt” language!

BTW, a photo of one of the signs can be found on this person’s blog post:

https://datkin.net/blog/2012/01/29/snowy-owls-and-eagles-at-boundary-bay/

Art Wolfe was recently there and supposedly leading a small group of photographers taking photos (https://blog.artwolfe.com/2012/02/snowy-owls-iii/) and I particularly found one of his responses to a reader’s comments very ironic. He talks about “respecting the habitat” but clearly he lead a group out into the marsh, something in conflict with the signs we’ve been debating. I pointed this out in a comment I left which has yet to be approved (though someone from Art Wolfe looked at it today (Hooray Google Analytics!)).

Tonight, as I was reading some more, I found this comment at a bird photography forum, from a staff ornithologist. It was in response to some photographers who were saying that flushing an owl is a minor nuisance. I like his response, since it takes into account the cumulative effects, not just individual behavior:

Michael, I really appreciate your background in BC, and your informed opinion on this location. Thanks for adding this element to the discussion.

I couldn’t agree with you more about the sensitivity of habitat in general, beyond the issue of the owls. I’m so accustomed to the habitat restoration efforts on my home turf of San Francisco Bay, I can’t conceive of trampling vegetation underfoot in this way. In places like Fitzgerald Marine Reserve, also near the Bay Area, there are serious restrictions on how far people can venture out into tide pool areas and so forth. I guess you could say I’ve been indoctrinated to stay on trail and observe signs, overt or subtle, irrespective of what anyone else is doing.

A photographer who was quite displeased with this post, had an email exchange with me, saying that the signs were mere suggestions, and that photographers such as himself are skilled and ethical enough to be out there in defiance of those suggestions. The “it’s not illegal” alibi seems to be the most prevalent. If you learn anything to the contrary, I would love to know. During hunting season, a number of photographers were incensed that hunters could be out in the marsh while they, supposedly, could not. I do see an issue of a double standard there, but I tend to avoid hunting season in the marshes, so I have no frame of reference in terms of where hunters are permitted to go at Boundary Bay.

The ambiguity in some of the signage (not all signs say “stay on trail”) is definitely problematic, relying heavily on the capacity of people to police themselves — which presupposes more personal restraint than I generally grant our species.

I love your idea for future measures. Do you think they would be responsive to those ideas? When I phoned the parks office, the person with whom I spoke expressed an element of exasperation, saying they simply cannot reign these photographers in, because their authority ends where the provincial land begins. I realize it’s a logistics and bureaucratic land management issue to which you can speak more readily than I, owing to your residence.

Steve – I do not see your comment – I guess it didn’t get through moderation. I was looking at Arts images a few days ago – trying to see if he had gone into the marsh. I am glad they kept a distance from the owls, but from his images I can’t say for sure they were out in the marsh. Those images all look possible from the path, especially with the long lenses I am sure he has.

Ingrid – There are a lot of habitat restoration efforts around Boundary Bay as well – both on the Canadian and US sides of the border. Perhaps our Canadian signs are just too polite! I do not know if the Ministry of Environment would be responsive to these ideas, but the media has certainly been all over it. Actually the only photographer I know by name that was out there photographing owls was outed on the 6:00 news here. I may ask him about those sorts of ethics in the future. So if I can’t get the Ministry interested next time I may point this out to the media and see what comes of it. At least from your questioning the city of Delta seems quite interested in not having people out there – even if it isn’t directly in their jurisdiction.

Hi, Michael, I’m sorry I made it sound as though the Bay Area was somehow exclusive with habitat restoration and protectiveness of wild areas. Mea culpa. That’s not what I meant to suggest, because disrespect of habitat areas is also a problem in California, especially in over-crowded areas like Fitzgerald Marine Reserve. I belong to a group here in Seattle that’s involved in estuary restoration, so I’m getting my bearings and education on Northwestern habitat issues. I’ve become quite passionate about the salmon projects, in fact.

I’ve seen plenty of bad behavior back home. It just seems to happen wherever humans congregate. What I intended to say was that understanding the sensitivity of that terrain, it’s difficult for me personally to venture off trail, even when others are. I can’t say the same would have been true when I was 20. I just didn’t have the awareness.

Your comment about the signage is one I might explore out of curiosity. I’ll have to go through my archives and see what photos I have of the signs in other areas. I do know that there is inadequate signage in many spots around SF Bay. I’ve had conversations with parks officials about installing signs that explain why people ought not throw rocks at birds and so forth. Yes, it appears that education is needed. I find it distressing, to say the least, that a sign which is polite, and which kindly asks people to behave in a particular way, might be disregarded precisely because it is polite. That’s a statement about human nature that I’m not sure I care to contemplate.

I did not take your comment as a suggestion the Bay Area had an exclusive on habitat restoration – I know these sorts of things go on all across North America. I was pointing out Boundary Bay as this is where we were discussing damage, and if it has to be restored… then it is being damaged.

I was pointing out Boundary Bay as this is where we were discussing damage, and if it has to be restored… then it is being damaged.

Thanks, Michael. When I re-read my note, it sounded that way to me.

Michael-

Yeah, although “someone” from Art Wolfe’s organization has made several visits to my blog and website, my comment remains unmoderated. Disappointing but not really unexpected. All I will add is that the sunset lighting on the bird’s chests and faces just seem highly unlikely from only the dike. I also saw another photo taken of one of Art’s colleagues who was with him during his trip and it’s clear to me that the individual is not on the dike. Oh well..

Steve, I agree with your sentiment: “disappointing but not really unexpected.” I know plenty of prominent bloggers who entertain and respond to controversial comments on their posts. I think it adds dimension to important discussions, even difficult ones. It’s a shame Art Wolfe or his moderators don’t see this as an opportunity to further educate or present important points on their methodology. I admit, it does color my opinion of people when they don’t allow scrutiny or opposing points of view.

I just wanted to tag some of these comments with a new link for the North American Nature Photography guidelines. This sheet is a great model for general field ethics: https://www.nanpa.org/docs/NANPA-Ethical-Practices.pdf

[…] photos and videos online which show the harassment of Great Gray Owls in Ottawa and Snowy Owls in Boundary Bay, B.C., Breezy Point, NY and southern Quebec, while many listservs are engaged in heated debates on the […]