FIELD ETHICS

My current set of standards and practices evolved from my volunteer work at a wildlife hospital, along with countless hours in the field. I’m grateful to the generous mentors who informed my work, and helped me become a more thoughtful and careful photographer.

Certified Community Active Wildlife Steward (Oct 2022) – in recognition of ethical practices

Member NANPA Ethics Committee (2016 – 2020)

Related Content: Blog posts on the subject of ETHICS

CONSERVATION

I regularly donate my work and time for conservation and scientific projects, including volunteer hours with wildlife organizations.

I have a particular interest in urban-wildlife intersections — the ways wild animals manage to exist or thrive alongside us, and in our structured environments.

One of my favorite themes is reclamation and resilience — how nature can revive, relocate, and restore itself when given the opportunity, space, and help to do so.

PERSONAL GUIDELINES

• As a former member of the NANPA Ethics Committee, I use the NANPA Ethics Guidelines and the Audubon Guide to Ethical Photography as models.

• I photograph with long lenses and a teleconverter. My primary wildlife lenses are the m.zuiko 100-400mm (which has an effective 800mm reach) and the m.zuiko 300mm f/4 (effective 600mm w/2x crop factor),

• I don’t bait or lure wild animals like owls or foxes (Note: these practices are not legal in many areas)

• I don’t use calls or decoys, electronic or other

• I’m extra cautious about nesting/denning areas (see below)

• In macro photography of insects, I do not stage or move animals for images, nor use any artificial elements (spray bottles, etc)

• I align with biologist Marc Bekoff’s term deep ethology: “Respecting all animals, appreciating all animals, showing compassion for all animals, and feeling for all animals from one’s heart.”

NESTS + DENS

Human presence near nests or dens presents various dangers. It can:

- Interrupt feeding, nurturing, and protective behaviors.

- In worst-case scenarios, it can lead to the endangerment and death of nestlings or baby animals.

- Humans can also create scent trails for predators, or alert predators to the location of babies.

Even pointing a lens at a vulnerable animal or nest can draw the unwanted attention of an observant predator.

There are some settings like urban heron rookeries, or carefully protected private or public sites, where photography of wild families can be done safely.

NATURAL LIGHT

I photograph animals in natural light, no flash. It’s less intrusive, and I enjoy the challenge of working with available light.

PROTECTING LOCATIONS

I’m protective of the wildlife I photograph. I frequently post just a general location, unless it’s safe to be more specific. I don’t reveal locations of uncommon animals or charismatic birds like owls which tend to be relentlessly pursued once their location is known. I also refrain from posting locations of animals considered targets, trophy or otherwise, by hunters during hunting season.

• Related: Wildlife Locations – When Sharing Endangers the Animals

ON ANTHROPOMORPHISM

In other animals, some behaviors are analogous to ours, some are obviously different. It’s as problematic to deny animals the feelings or intelligence they possess, as it is to anthropomorphize them. They have unique entitlement to their own lived experience which we can only observe and try to interpret, imperfectly.

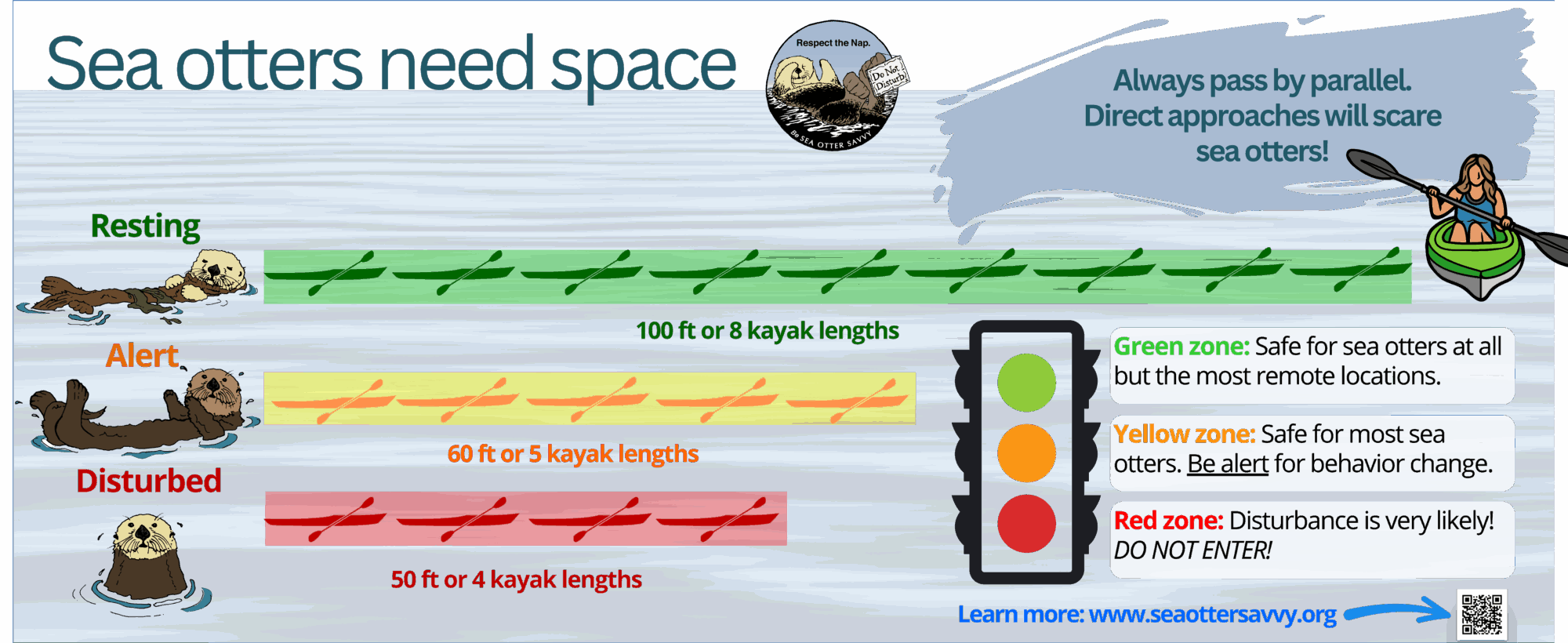

STRICT ETHICS WITH SEA OTTERS

If you’re on the Central Coast of California or in other locations where sea otters are present, please do not disturb them in any way, (from water or shore). Southern sea otters in California are a threatened species, and human disruption causes significant problems for them. Sea Otter Savvy shares important observation guidelines: Be Sea Otter Savvy #RespectTheNap